Martintxo Mantxo

Main photo: Indigenous people protest in Rio against the auction of oil blocks in Margem Equatorial and Abrolhos.

(Castellano) (Euskara)

The news shocked the country: less than a month before Brazil hosts the 30th Climate Summit in Belém, Pará (COP 30), Lula’s government has authorised oil exploration off the coast of the Amazon estuary, sparking protests.

How can this happen when that government has declared itself a leader in the global fight against climate change? When this summit is so important? What happened to its plans to become a climate leader, when it said a year ago (November 2024) at the G20 Summit that ‘We need stronger climate governance’? When he said at COP 28 in Dubai that we need to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels. What message is Brazil sending to the world when it has mobilised other countries to attend the COP and make commitments?

Ironically, today (24 October) in Indonesia, Lula claims that Brazil is a leader in clean energy (which is also highly questionable, as many fuels are obtained from crops, which has serious environmental and social impacts) and that exploration in the Equatorial Margin will serve to drive the green transition. This is the same duality that we find everywhere in this system: we promote renewables but continue to consume fossil fuels, or, as in this case, we intensify their use. Or what is understood as greenwashing, renewable energies and supposed environmental commitments serving to clean up the image of fossil fuels. Today (24 October 2025) in Indonesia, Lula adds to these statements: ‘Brazil will be a global example in the energy transition during COP30’.

But the other reason for promoting this inconsistency may lie in the government’s economic situation, which requires an additional 27.1 billion reais (4.326 billion euros) to meet its fiscal targets. In this case, oil exploitation could be justified not from an energy point of view, but from an economic one. Estimates are for 10 billion barrels of oil that could potentially generate 420 billion reais (67.27 billion euros).

However, Brazil has already added significant oil and gas production to its economy, much of which is destined for export. As Nicole Oliveira, director of the Arayara Institute, explains in an interview in Brasil de Fato, ‘Brazil exports between 40% and 45% of the oil it produces, so it’s a fallacy.’ (More here: Amazonia Livre de Petroleo)

In this sense, we will find ourselves in the same situation that many oil-producing countries have experienced before, in which their production, while promising to be a source of income at first, becomes a problem because, in the face of new investment opportunities, inflation and debt arise. This is known as the Resource Curse. In this case too, despite national control of production through a state-owned company and the supposed controlled destination of profits, oil would continue to be a false economic solution.

In addition to economic needs and the desire to achieve higher levels of progress, the exploration and future exploitation of offshore deposits in Margem Equatorial correspond to the constraints of peak oil, the depletion of deposits and resources as we consume them. At this point, companies and governments are taking greater risks and launching projects that were previously unfeasible (not only technologically). This is driving extraction at great depths in the sea (one third of the oil extracted already comes from these platforms), in remote and vulnerable areas of the rainforest, or using expensive and dangerous technologies such as fracking.

Threat to the environment and indigenous peoples

In addition to climate impacts, there are other environmental impacts. The only way to check for oil is by drilling. When drilling, the main risk is the possibility of an oil spill, which could significantly affect local marine life, including coral reefs.

This is one of the most environmentally sensitive regions on the Planet, classified as a Priority Area for Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Conservation. It is home to unique ecosystems such as the great Amazonian reef system and more than 80% of Brazil’s mangroves. It is also an area of great fish wealth, on which the food security of thousands of families depends.

Within these populations, this exploration threatens the indigenous communities that inhabit the coast. The Oiapoque indigenous protected area is located on this coast, inhabited by the Karipuna, Palikur, Galibi Marworno and Galibi Kali’na peoples. In addition to the direct impacts of exploration and subsequent future exploitation, we must remember that indigenous peoples are also the most vulnerable to the climate crisis and its effects, such as pests, extreme weather events (droughts, floods, cyclones) and others that result from these, such as fires or sea level rise in the case of those living on the coast.

The leader of Oiapoque and the Articulação dos Povos e Organizações Indígenas do Amapá e Norte do Pará (APOIANP), Luene Karipuna, uses a play on words to express her rejection of the project: ‘Our territories are tired of being explored,’ alluding to previous colonialist exploration and current oil exploration.

‘Will we be a new Belo Monte? Will we be a new Yanomami territory explored, destroyed and pressured?’ Karipuna continues. Both are indigenous territories that have suffered a major environmental impact: in the first case, it has directly or indirectly affected 20,000 people, including displacement, or even genocide due to pollution, epidemics and harassment in the second. In Belo Monte, the disaster was caused by what was the second largest reservoir in the world, while in Yanomami territory the problem was created by illegal mining. Coincidentally, Belo Monte was built during Lula’s previous government. In the Yanomami case, the biggest crisis occurred as soon as Lula took office, but it was the result of the policies of his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. Lula travelled to the indigenous territory and described the situation as genocide, declaring that his predecessor was ‘a government insensitive to the suffering of the Brazilian people’ and declaring his government’s commitment to indigenous rights.

The result of this commitment was the creation of the new Ministry of Indigenous Affairs. But as Karipuna questions, what good is a ministry if indigenous rights are not respected? As she also said, indigenous peoples, unlike marine animals, have not been considered, nor are they even included in the Contingency Plan for this oil exploration project.

Brazil not only has great biodiversity, but also great cultural diversity, as no fewer than 391 different peoples (some uncontacted) (295 languages) inhabit its territory. The Brazilian government should not only protect this legacy, but also take it as an example, and instead of aspiring to higher levels of consumption by imitating capitalist parameters, it should promote indigenous values and lifestyles (Buen Vivir – good living) and be a reference in this field. The Planet needs to decrescent, and Brazil has the culture(s) and tools to do so.

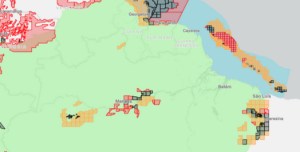

A large extractive area called Margem Equatorial.

The project granted is for block FZA-M-059, in the Margem Equatorial area. It is located 500 kilometres from the mouth of the Amazon River and 175 kilometres from the coast, in deep waters off Amapá, at a depth of up to 2,500 metres.

With this project, Petrobras and the government hope to prove the existence of oil, which will then, obviously, be extracted and consumed. Ironically, it is Ibama (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis), which reports to the Ministry of the Environment, headed by Marina Silva, whom endorsed the decision. Silva has returned to this government after previously leaving Lula’s government from 2003 to 2008 due to environmental disagreements over biofuel and hydroelectric energy policies.

This decision does not help much on the eve of the COP. It delegitimises attempts to decarbonise. It is not that Brazil, despite its large production and use of bioethanol and biodiesel, is exempt from fossil fuel production: in July 2025, Brazil exceeded its historical maximum oil and gas production with 5.16 billion boe/d (barrels of oil equivalent per day). Most of this oil (92%) comes from deep and ultra-deep waters, mainly from the Pre-salt field 2,000 metres below the surface off the country’s southern coast.

It should be remembered that the Pre-salt was discovered during Lula’s government (2007) and that its exploitation was directly promoted by his government and later by Dilma Rousseff’s. In his speeches, Lula always stated that the money resulting from its extraction would be reinvested in Brazilian society and in social projects, and that it would be exploited by the state-owned company Petrobras. Without excluding money pocketed by individuals, because in the oil industry spills are also of this type, and the defrauded, as happened in the 2014 Lava Jato scandal at Petrobras.

However, it should be borne in mind that, in addition to involving large quantities of oil being burned, polluting and contributing to climate change, drilling at such depths carries great risks, as has been demonstrated on numerous occasions, with the possibility of spills into the sea. In the year the company was created to exploit the pre-salt layer (2010), the largest offshore extraction accident occurred in the world, that of the Deepwater Horizon platform in the Gulf of Mexico.

This July, however, Ibama rejected Petrobras’ request to undertake the fourth phase of pre-salt exploration. Apparently, this request lacked a climate action plan. Now, what climate action plan can an oil exploration project have?

The seriousness of this decision is not because of what it implies in itself, but because it opens the door to other projects. The coast of the Margem Equatorial, where the mouth of the Amazon is located, has been divided into blocks that this government has already proceeded to sell to various companies. If this continues, Exxon Mobil and Chevron will also be operating alongside Petrobras. These companies acquired blocks when this government auctioned 47 blocks on 17 June this year, of which 19 were purchased.4

It seems as if they were waiting to approve it so close to COP30, because this project has a long history of rejections. They have been trying to push it through for years. In 2018, Ibama already rejected an application from the oil company Total and in 2024 from Petrobras.

In addition to Arayara, the Federation of Oil Workers (FUP) itself has filed a lawsuit on the grounds that these tenders violate Brazil’s environmental and climate commitments. It is good to see this position taken by the oil workers’ union itself, which, at least, remains faithful to its principles. The FUP advocates converting the oil industry to renewable energy, to provide society with clean energy, but also in a democratic manner.

Oil in the soil – Leave oil underground.

The COP to be held in Brazil should ratify the decisions of previous COPs. Although there have not been many, we have to go back to COP21 in Paris in 2015 to find the most substantial proposals. It proposed not exceeding a global temperature increase of 1.5 °C to avoid irreversible impacts on the climate. To this end, even then, many experts advised that the only way was not to start new extraction projects: leave the oil in the ground. This has been the slogan of Oilwatch, the international organisation of people and communities in the Global South affected by oil extraction.

One of the milestones of this campaign was undoubtedly the attempt to prevent drilling in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park (Block 43 ITT). This attempt, initially endorsed by the Correa government, later suffered a setback with its tender. In this way, as now, priority was given to making oil extraction profitable over its environmental and social damage. In this way, a progressive government, as now, betrayed its previous principles. In August 2023, a new referendum was held, with the result once again in favour of keeping the oil underground: 58.95%. Accordingly, 246 wells must be dismantled in five years and five months (10 of them, considered for immediate abandonment, were eliminated in 2024). Starting this year (2025), 48 wells per year should be plugged. But the Waorani people who inhabit the area have already mobilised to protest the slow pace of dismantling.

In Argentina, opposition to offshore oil exploration was organised around the Atlanticazo movement, which successfully defended the sea. In Norway, popular opposition also managed to halt coastal exploration in the Arctic Circle. In Brazil, opposition has not been as vocal.

Social mobilisation in the Canary Islands, Spain, also succeeded in stopping Repsol’s attempt to start oil exploration between 2011 and 2015. Once again, the environmental threat was very great. This April, the Cabildo of Gran Canaria also rejected gas and oil exploration by Morocco (with Israeli companies!!!) near the Canary Islands.

New hiCOPresy?

Ten years after that Paris summit, the 1.5°C target seems unattainable, and experts believe that the planet will warm by around 2.5°C by the end of this century. Therefore, the summit to be held in Brazil should present serious measures. Thus, we fear that this COP will unfortunately continue in the footsteps of the previous ones in Azerbaijan (COP29) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (COP29), characterised by the interest of their hosts in reaching agreements that did not pose a risk to their fossil fuel extraction policies.

NOTES:

3Santa Barbara (California) 1969, Montara (Timor Sea) 2006, in the North Sea in 1988 Piper Alpha and in 1980 Alexander L. Kielland, Bohi 2 (sea between China and Korea) 1979

4 Leilão da Foz do Amazonas: oil companies win 19 of the 47 blocks

5 https://exame.com/esg/leilao-na-foz-do-amazonas-19-blocos-vendidos-dos-47-em-meio-a-eztabaide-ambientais