By A Planeta based on information from MAB and Brasil De Fato (Castellano)

This May, the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in southern Brazil, suffered the worst floods in its history, with 149 people dead, more than 100 missing, and two million people affected. The volume of rainfall in recent days reached 800 millimetres. Although this rainfall was predicted in advance by the meteorological institutes, rivers and lakes overflowed their banks, flooding hundreds of villages.

But we are also facing recurrent phenomena, because similar situations were already experienced in September last year. In June 2023, the floods caused another 116 deaths, in September 54 deaths, and in November five more deaths.

In the case of the Taquari valley, this is the third time in less than a year that the region has been devastated by floods. Residents still trying to rebuild their homes and crops after the floods of September and November 2023 saw the Taquari River rise above 30 metres. In this valley, on 2 May, the rains caused the 14 de Julho reservoir to partially burst, creating an added risk.

Two factors converged in these floods: an economic and growth model with a major impact on the territory and the environment, and on the other hand the extreme weather phenomena resulting from the climate crisis (obviously also caused by the same economic model). Or we could add a 3rd, the product of four years of a government, that of Bolsonaro, a climate denier who has also promoted the dismantling of environmental policies, passive in prevention policies, and as we know, promoting deforestation and the elimination of ecosystems.

This economic model includes the impacts of agribusiness, which leads to deforestation, which in the state of Rio Grande do Sul has increased by 187% in three years. Also urban policies that have not respected boundaries and have fallen victim to real estate speculation. Both correspond to a model of unsustainable development that Naomi Klein has called «disaster capitalism», discussed in her work «The Shock Doctrine» (in itself, this episode has much in common with the New Orleans disaster that she discusses in depth).

Rio Grande do Sul was built on the banks of rivers and lakes, with millions of people living in at-risk and very high-risk areas. Many will now have to be relocated, and many more need warning systems such as sirens. A 2019 study already warned of 700,000 Gauchos living in at-risk areas. Millions also live in areas at risk of landslides in the mountains of this state and others. After the Guaíba River burst its banks in 1941, a 6-metre wall with floodgates was built in the 1960s and 1970s to contain it. But even that has not been able to hold back these volumes.

The city of Porto Alegre has become the capital of agribusiness, a regional economic and financial centre of attraction, urbanistically out of control. The countryside is unable to absorb the rain and the big city is unable to evacuate all the water that has fallen. Yesterday, 23 May, a request was made for the dismissal of the mayor of Porto Alegre, Sebastião Melo (MDB) for «the negligence of the City Council in the care of the Pumping Stations and the urban drainage system of the city».

Preparing for a time of climate extremes

Climatologist Carlos Nobre was interviewed by Brasil do Fato. He clarified that the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions is not an option, nor a choice, but is «absolutely mandatory. If we don’t manage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly, we could reach 2.5°C [global temperature increase] by 2050. This will make these extreme events much more frequent, heat waves, rains, droughts, a huge impact on all natural systems, a huge impact on biodiversity and our very survival.»

«Rivers were never supposed to rise much, which we already saw in September last year in the Taquari river basin, which rose more than 10 metres. And now, again, in some places, up to 20 metres. So there is no way to imagine keeping all these populations in these very high-risk areas».

Cemaden (Centro Nacional de Vigilância e Alerta de Desastres Naturais) is to present in the coming months a study that has tracked more than 1,900 municipalities across the country where there are records of people living in at-risk areas.

According to Nobre, the number of Brazilians in at-risk areas is likely to exceed 15 million, with some 4 million in very high-risk areas, such as those living along the banks of all those rivers that overflowed their banks. These people should be relocated.

Extreme weather events such as recessionary and severe rains, very dangerous wind gusts, droughts, heat waves, vegetation fires, crop failures, occur more frequently and also with more virulence. As the climatologist explains, as time goes on, records are being broken: «In the Taquari river basin, in September last year, there were record floods in the history of that basin. And now, last week, and continuing this week, there have been record floods and many landslides all over the state of Rio Grande do Sul, more than 60% of the state has been affected. We have seen this all over the world. In 2023 and 2024 we had record breaking drought in the Amazon and now this summer in the Cerrado. In 2020 there was a record drought in the Pantanal. All these things that are happening, the record heatwaves around the world and also in Brazil in recent years, are extreme phenomena, which are not only happening more frequently, but records are being broken practically all over the world.»

Globally we are also breaking records: «Last year was the warmest year on record in 125,000 years, since the last interglacial period, and this year is still as warm, or even slightly warmer than the last. The oceans have broken all temperature records in history, at least until the last interglacial period of the last 125,000 years. So there is no way to imagine that these phenomena will stop occurring, or that they will occur less frequently. On the contrary, they will occur more frequently.

For Carlos Nobre, the solution lies in «trying to increase the resilience of all populations, protect biodiversity and also make agriculture much more sustainable, this is a challenge for everyone, for Brazil and for Rio Grande do Sul, a state that is a super agricultural producer. Several policies that are being implemented in Brazil go in the opposite direction. There are policies that allow deforestation to increase, that allow degradation to increase, that allow vegetation to be removed from riverbanks. All this is happening, unfortunately, in many states in Brazil. Even in Congress, with federal legislation».

Brazil will host COP 30 in Pará in 2025, so it has a big challenge ahead to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and also to prevent associated damage. And at the international level, Nobre believes that COP30 will have «a huge responsibility to show the risks, because from COP 27 in 2022 to COP 30 here in Brazil in 2025, extreme events have skyrocketed around the world. So let’s hope that Brazil will lead a big transformation, so that we rapidly reduce emissions by 50% in the next few years, and then zero emissions by 2050».

«With current emissions, we could permanently reach a global temperature increase of 1.5°C by 2030,» explains Nobre. «Imagine the Paris Agreement, very well done, reinforced at COP 26 in Glasgow in 2021, saying, «Look, we can’t let the planet reach 2°C, it’s too dangerous. We’re not going to let it go beyond 1.5°C», the truth is that we are already reaching 1.5°C. To stay within 1.5°C, we would have to reduce emissions very quickly. Almost 50% by 2030, and then net zero emissions by 2050, is not an easy task. If we take what every country pledged at COP 27 in Egypt in 2022, we would reach 2050 with 2.4°C to 2.6°C.»

Dams increase flood risk as climate events intensify

According to experts, Brazil needs to review its dam safety system to avoid collapse in the face of the country’s new climate reality. Brazil’s National Dam Safety Information System (SNISB) warned that 2,946 of the country’s 26,000 dams are at risk of collapse. In Rio Grande do Sul, following the floods, the Bugres hydroelectric plant (CH) was at imminent risk of collapse. In the rest of the country, other reservoirs were on alert, such as the 14 de Julho hydroelectric plant, which has already suffered a partial collapse in Bento Gonçalves, the Dona Francisca hydroelectric plant in Nova Palma and the Salto Forqueta plant.

According to Alexania Rossato, a member of the coordination team of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB), the climate extremes that have intensified in Brazil are causing additional concern to people living near dams at risk of collapse.

As always, these people are the poorest, those who lack the resources to choose another house, those unable to move away. The poor suffer the most.

In 2019, MAB warned of the dangers of relaxing environmental legislation in the state of Rio Grande do Sul for the well-being of the population and the protection of the natural environment. As they explain, «in 2019, Governor Eduardo Leite (PSDB) revoked the decree that regulated the State Policy for Those Affected by Hydroelectric Projects in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The law provided for the implementation of security and reparation measures for communities living near dams. In other words, it was a legal instrument that could be used to guarantee the protection of the lives of affected people, through inspection actions, the creation of emergency plans and the participation of the population in the formulation of disaster prevention policies, among other guarantees».

These floods affect the solid parts on which the wall of the dams are cemented. The impact of these phenomena is cumulative and, as we have already reported, many municipalities in Rio Grande do Sul have already suffered major floods up to three times in the last year alone.

Regina Alvalá, PhD in Meteorology and deputy director of the National Centre for Monitoring and Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN), points out that many dams in Brazil are close to densely urbanised areas, such as in the state of Minas Gerais and in the north of the country.

Leonardo Maggi, also a member of the MAB coordination team, explains the risks of the Lomba do Sabão dam on the border between the municipalities of Viamão and Porto Alegre: «It is a dam built in the 1940s, which was decommissioned 10 years ago and has since been abandoned by the neoliberal mayors who have succeeded each other here in the capital». According to him, the risk increases with the current extreme events.

The MAB coordinators stress that the engineering of the dams was designed with historical rainfall statistics in mind that are very different from the current scenario. «There is a new reality of extreme concentrated rainfall, a new situation that was not in the statistics at the time the large dams were designed. Therefore, all dam projects, whether hydroelectric, water supply or tailings, need to review their safety systems to take into account the new climatic reality,» argues Gilberto Cervinski, a member of the MAB coordination team. He explains that there is a safety margin in dam projects, but that it takes into account normal statistics. «Now it is an abnormal situation and, in this new reality, we cannot say whether they are safe or not. As we don’t know exactly where the next big rains are going to come from, we have to analyse them all».

Leonardo Maggi also denounces that «this mix of precariousness, abandonment of these structures, irresponsibility, lack of supervision by the state makes the area around the dams a place of exclusion, a place of suffering, a territory of suffering for the people who live near these structures».

Climate change adaptation plan shelved in Rio Grande do Sul

Maggi stresses that, in the case of the municipalities of Rio Grande do Sul, the environmental problem caused by dams is aggravated by the dismantling of environmental policies. In addition to repealing the Policy for People Affected by Climate Change during his previous term, Governor Eduardo Leite reduced the budget for Civil Defence, shelved the State Policy on Disaster Risk Management, and ignored mitigation and adaptation measures recommended by scientists hired by the state itself.

Nor did the floods that devastated the Taquari Valley last year, which left dozens of people dead, motivate major prevention efforts. «In eight months (since the last flood), not a single house has been built and the planned relief actions have been completely incapable of saving lives now. Has the state structure not learned from climatic phenomena,» asks Maggi. «This situation we are experiencing is also the result of the herd that passed through the Bolsonaro government, with the dismantling of environmental legislation. This catastrophe that happened today affects millions of Brazilians and thousands of Rio Grande residents,» he adds.

This activist also associates the overflows in the capital of Rio Grande do Sul with poor public management. In the 1970s, the flood containment system for the Guaíba and Gravataí rivers was inaugurated, with 14 floodgates and 23 suction pumps. The system was designed to withstand floods of up to six metres. «But with a rainfall of 5.30 metres, the system has already broken down. Why has it broken down? Because it did not withstand 20 years of municipal governments that did not do the maintenance, that did not adequately control this anti-flood system. Of the 24 pumps installed, only four worked. This shows the level of neglect of the system,» argues Maggi.

«Until almost the end of the last decade, we used the verb conjugated in the future. In the future, climate events will be more intense, more frequent. And what we are seeing in this decade is a confirmation of what was predicted: the events are already more extreme,» he stresses.

For Regina Alvalá of Cemaden (Centro Nacional de Monitorización y Alerta de Catástrofes Naturales) deaths are not only the result of so-called natural phenomena, but of a combination of factors: «threat, exposure, vulnerability, capacity or not to face the challenges, mitigation, etc. So, if you have increased the level of hazard, which is torrential rains, if you don’t reduce vulnerability and exposure, obviously disasters are going to have a greater impact».

In addition to climate change adaptation and mitigation policies, MAB coordinators advocate that governments should also implement policies on the rights of affected people in the country (whether state laws or the federal regulatory framework), to ensure the prevention of further major disasters. In December 2023, President Lula approved Law 14.755 of 2023, which establishes the National Policy on the Rights of Dam Affected People (PNAB). The aim of the law is to guarantee the rights of those affected and to reduce the risks imposed by the projects and other damages caused to the population, such as forced displacement, loss of income, water contamination, impact on mental health, among other serious health and environmental consequences.

This law, as Cervinski explains, ensures «the right to compensation for losses, the right to information about risks, the right to resettlement, the right to participate in negotiations to rebuild their living conditions and reduce risks».

In this context, Regina Alvalá points out that the involvement of the population in this moment of prevention and reparation of the affected territories is fundamental. «In addition to the three levels of government, we also have to involve society. Because, in the end, it is human beings who are most affected, it is the population. So it is essential that efforts are capitalised so that this risk management, which is mandatory, is carried out in a more organised and participatory way.»

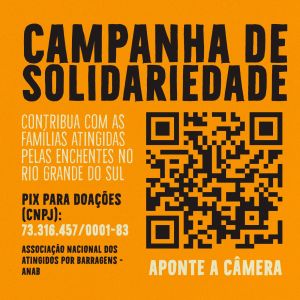

Solidarity

As on many other occasions when human catastrophes have occurred, MAB has articulated its powerful movement, infrastructure and levels of solidarity to attend to the people affected. For although, as their name suggests, they are concerned with people «affected by dams», their awareness and capacity makes them go beyond that and assist people affected by other causes. In this case, MAB has mobilised its kitchens and activists to provide food to affected people. They are also facilitating other types of aid, so our solidarity is also essential.